Elvis Presley, Andy Warhol and Marc Bolan walk into a bar. If it’s the early seventies in Los Angeles, it can only be Rodney Bingenheimer’s English Disco. Rodney Bingenheimer was ‘The Mayor of Sunset Strip’ and, from 1976, ‘Rodney on the ROQ’. The ROQ was KROQ, Pasadena radio station and pulpit for ‘tastemaker’ Rodney for 40 years. Rodney on the ROQ broke Blondie and the Ramones and introduced America to the Sex Pistols and the Smiths.

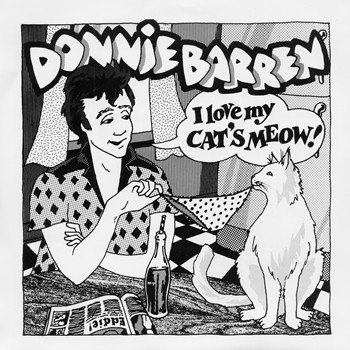

In the summer of 1983 he put a new German singer on a path to brief global domination. Nena’s “99 Red Balloons” was top of Rodney on the ROQ’s chart for a month. The song it succeeded at number one had been there twice as long. It was Donnie Barren’s “I Love My Cat’s Meow”.

In mid-sixties Woodland Hills, California, Don Holtzinger (Donnie Barren or “dB” would come later) and his first band of brothers – four sons on trumpet, saxophone, drums and clarinet – would play in white tuxes to a few hundred at salesman dad’s Christmas parties. Fast forward school years, past a brief piano-playing interlude, to a broken leg (ski bum season, Colorado) and a full leg cast for five months. With the rapt female attention that older brother Doug’s playing would attract still fresh in his mind, Don settled in to learn to play guitar.

The guitar has left Don with a blind spot for late seventies popular culture. While friends were taking in Alien and Apocalypse Now, Don was “woodshedding”, musician-speak for incessant practice. Leg mended, he sold exercise equipment door-to-door while graduating from acoustic to electric to lead.

Soon enough, it was time to face an audience. Almost. A shy performer, he played his first gig, in a neighborhood backyard on a hot summer Saturday evening in front of twenty or thirty people, determinedly facing the back fence. Fast forward a couple of bands, and a drummer friend took him aside. Own the stage. Take your solos. Give them a show.

A few short months later, photos show a different Don. There are flowing locks, a white sailor suit and red neckerchief. Playing his Les Paul Custom in Tobacco Sunburst with his teeth. Carried high on the singer’s shoulders, shredding, whooping, hollering. Giving them a show.

Early eighties Southern California high schools were into rock in a big way. Students, of course, but principals too. Their assemblies, lunch hours, proms and homecomings needed livening up, and a sprinkling of Van Halen-y stardust fit the bill. Donnie Barren (middle name Barren had stronger rock credentials and fit better on his custom guitar picks) and new band City Lights hit the high school circuit, armed with the Rick Nielsen/Cheap Trick playbook. Stagecraft and stickers, buttons and buzz, live and local. They built a mailing list of several thousand. Complimentary tickets if you filled in a postcard. A free record for a lucky few at each show. Different buttons at different gigs – collect the set.

Their fanbase made them a big enough draw for bookers at the Troubadour, the Whiskey, the Starwood. Headline shows, people turned away at the door. They shared a stage with X, Oingo Boingo, members of Rod Stewart, Elton John and Jeff Beck’s bands. They played with Dokken, Ratt and versions of Quiet Riot. The metal bands brought the noise, City Lights brought the high schoolers – pop for the girls, rock for the boys.

Everyone had a day job so every cent they earned playing was ploughed back in. They invested in bigger speakers and better lighting. They upgraded their wheels to an old bread truck. They bought late night time at Skip Saylor’s studio and put out a couple of records, a single and a 5-track EP. The ‘Blackout’ EP featured three Donnie Barren vocals and a Zombies cover. Songwriting duties were shared between Donnie and keyboard player George. Both would write to make space in the song for the other; Donnie’s songs would often feature strong keyboards, George’s solid guitar parts.

High school bathroom mirrors bloomed with City Lights stickers. Telephone poles grew a thick skin of City Lights flyers. Lunchtimes got crazy. One student, trampled underfoot, broke an arm. A six-foot high City Lights logo surfaced on a Route 101 flyover in LA thanks to a passionate fan armed with spray paint and sturdy rope. Hard to reach, it took city cleaners years to shift it.

The graffiti outlived the band.

For one thing, Donnie says, “we weren’t that sophisticated at business”. Friends had always rallied round. The keyboard player’s girlfriend wrote out the lyrics for the cover that Donnie’s roommate designed, while their sound man, lighting crew and roadies (this was a serious live outfit) got rent-free digs. But they’d sunk real money into making the record and tried to recover their costs from local record stores. Looking back, “if we were sophisticated, we’d have given it to the record stores for maybe five cents and they could sell it for five dollars. Because making money at that point wasn’t important, it was getting distribution.” Timing was not on their side. Shoulder surgery took Donnie out of action for a few months just as new wave pushed rock guitars aside for a while. After burning brightly for a few short years, the City Lights went out.

It was 1982 and Donnie Barren, undeterred, went solo.

His one-man marketing engine kicked into gear. Mailers from Derek Scott (his brother’s first and middle names) went out to radio stations and promoters, talking up Donnie Barren, ‘the new solo project from City Lights’ singer/guitarist’. A new review would mean a new mailer. He loitered around radio stations and pitched the dance clubs (who, along with Rodney, were breaking Duran Duran in America). The new single he was pushing, “I Love My Cat’s Meow”, was a bit risqué. Berlin’s “Sex” and “Hungry Like the Wolf”’s gasps and moans were getting airplay. And Rodney on the ROQ bit. The first time Donnie heard his song on KROQ, he was filling up at a gas station. He danced around the forecourt, exhorting strangers at other pumps to listen.

Radio play could get the ball rolling. But radio stations would then want to know if people were buying it. He needed distribution. When Rodney on the ROQ got behind Cat’s Meow, record label Faulty Products got behind Donnie. Faulty Products (Bangles, Black Flag) was part of I.R.S. (R.E.M., the Alarm) which was part of A&M (the Police, Bryan Adams). But, inevitably given rock and roll cliché, just when things were heating up, finances failed and Faulty folded.

An A&R friend at Polygram believed, but needed an album to shop around. Four months and several all-night studio sessions later, new songs like “Can’t You See the World Through My Eyes” and “‘Til the End of Time”, and a pre-Tiffany cover of “I Think We’re Alone Now”, were ready to roll. But the moment had passed, and so did the record companies.

Donnie kept toiling away. He had always invested in his singing, his production and his songwriting. When he first started out, he paid songwriter Jerry Gladstone (Ray Conniff, Johnny Mathis) to critique his early efforts. Now he started co-writing, first with 16-year-old Charlie Sexton (prodigy, razor-sharp cheekbones), then with Tom Petersson (Cheap Trick) and Shandi Sinnamon (Flashdance, The Karate Kid). Tina Turner looked but ultimately passed on Shandi and Donnie’s song “I’ll Dance Alone”.

Donnie always nurtured his business acumen; his depression-era dad had drummed the need for a fallback into his son from an early age. To stay in the music industry’s orbit, he took a job working for a rock promoter, keeping his books. The promoter’s way into the business had been a Harvard MBA. Donnie looked up what an MBA was and called Harvard. First question: “Where is your undergrad from?” Donnie hung up and got down to it. He wrapped up his long-paused degree in 18 months (night school, straight A’s), then it was the GMAT and – long pause for Harvard’s response – he was in. The idea was to use his MBA to get a mighty job at a mighty record company and use his might to get his songs out there. He started out in brand management at Procter and Gamble, then a renowned finishing school for marketers. Although he sometimes had input on the songs picked for TV commercials, he was on the fringes of the music side of the business and, soon enough, it was “life is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans.” Donnie reflects, “It was hard to do it all and I finally came to this realization that, if I want to move forward, I’m going to have to set something aside for a while.”

Two decades passed before his creative itch got another scratch. New technology and techniques – say hello WAV, goodbye tape splicing – allowed him to start tinkering with new music at home in the Pacific Northwest. And he went back to the woodshed. Literally. His solo album had sat on a moldy shelf in his garden shed on quarter-inch tape for over twenty years. Still intact, he turned it digital and put it out on CD and iTunes, primarily so his family (wife Becky, daughter Meg, and son Clay) could hear it.

He found room for a home studio in a remodel around 2010 and started putting the hours in. Evenings after work and dinner were for making new music, although, true to character, he worries the recording cost him precious family time. He joined a local band playing original songs and released a Joe Satriani-inspired album (“Freedom”). And then “sync” became a thing.

In the music industry, there are ways to get heard, and ways to get paid. Until a song’s been documented, it’s hard to do either, beyond playing live. Getting the musical composition down creates a song copyright. Recording it creates a sound recording copyright. Once the song exists physically or digitally, it can go out and make its way in the world.

The way a song makes money depends on how it gets out there.

A mechanical license covers a song getting out there on a piece of plastic (or, now, as a download). Standard song rate for plastic is 9.1c per record. If someone covers “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door” and presses 1,000 copies, Bob Dylan is owed $91.

A public performance license covers the song getting aired in public. In the US only the song and not the sound recording earns. That’s why, when Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You” loops in your local mall, Dolly Parton gets paid, Whitney’s estate doesn’t.

Record companies, distributors, publishers and PROs are the major players in the world of mechanical and public performance rights. Distributors get physical products out there. Record labels bankroll and promote artists. Publishers manage the song rights and PROs (Performing Rights Organizations) collect the money that’s owed when the music plays. This was pretty much the music industry in 1983.

But we don’t hear new music in the same way today as we did then. Music radio audiences have been declining for years. MTV is not about music anymore. Spotify and Apple Music stream whatever we want. But who breaks fresh music today? Enter voracious new media beasts. Video games, streaming shows on Netflix, Amazon Prime, Hulu, and, yes, still advertising. They all need tunes that fit the mood and sell the message, and music supervisors are responsible for getting them.

That’s where ‘sync’ comes in. Music supervisors still go direct to the labels for a lot of commercially released music but, increasingly, music libraries find songs that content creators need, secure the ‘sync’ licenses needed to fold music into another medium, and sell them in. The makers of Netflix movie “Someone Great” need new music for a pivotal scene, or TikTok needs a song to go with their #DNATest challenge, and hey presto Lizzo breaks out. The makers of “Big Little Lies” need a theme tune, and Michael Kiwanuka finds an audience. For a lucky few, sync is the new Rodney on the ROQ. And it’s a way for a 1983 song and its singer to get another hearing.

Enter TAXI, one of the new music intermediaries Donnie works through. They’re a bridge to music libraries and music supervisors. Donnie can work to order. Something needed next week for a bar-room scene, sounds like George Thorogood and the Destroyers, and he’s on it. He is becoming his own stable of artists, different styles and sounds.

In the spring of 2018, TAXI put out a call for authentic eighties rock. Music supervisors of a popular Netflix show set in early eighties America were looking for songs. They didn’t want anything written to order, only originals from the time. They needed a song to serve as the backdrop for a scene between a showbiz manager and his daughter and ex-wife at, where else, a high school dance.

He knew a month ahead of time that he’d got it but kept the news close until it aired.

If you check out the soundtrack to GLOW Season 2, you’ll find Madonna , The Human League, Hall and Oates, Run DMC and Billy Joel.

And there, rubbing shoulders thirty-five years on, you’ll find Donnie Barren and “Can’t You See the World Through My Eyes” from the album that missed its moment.

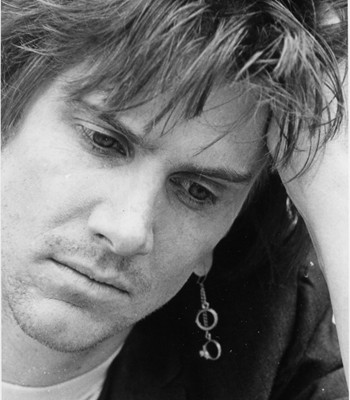

If you’d met Don during his business career – he served a long and successful stint at Microsoft after Procter and Gamble — you’d have encountered a kind soul, a capable and creative executive with short – but not too short – hair. Donnie today is easy and generous company, with longer, grayer hair, and an undimmed passion.

Donnie’s life in music has been a lot of ebb and some sweet moments of flow. Forty years after he started out, digital has changed almost everything. In 1980, a band of City Lights brothers hunkered down to write, rehearse and record together. Their two-track tape became a silver platter that they walked into Rainbow Manufacturing and, a week later, everything they were about was etched onto a piece of black plastic. Today he collaborates with songwriters in Germany, Canada and Australia who he’s never met. He’s adamant that a great vocal sells a song and the needs of the song come first, so professional singer friends in Seattle, Nashville or LA lay lead vocals over the digital files he sends them. A new song can be heard, anywhere in the world, the day it’s done. While so much is different, it still comes down to guitars and a great hook.

Donnie Barren is still in the studio most days. He’s just put in a 6pm to 6am shift to hit a deadline for a song submission. He can’t really put his finger on why he did it, why he does it. It’s certainly not for the rewards – Madonna will have devoured the lion’s share of the GLOW music budget. Clearly, he loves making music. But he also just wants to be heard.

And that’s all it was ever really about.

Donnie Barren’s website.

Donnie on Spotify.

Donnie on Facebook.

This is a great journey of the “Microsoft-Donnie” I knew back in the late 90’s. A great story and one to be extremely proud of, Don-nie! Should have gotten your autograph—is it too late?!